The biblical story of the Babel Tower had long been the explanation for the variety of languages observed in the world. The similarities between some of them have been noted hundreds of year ago, e.g. by Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada in his work De rebus Hispaniae (1243). Since that many different efforts have been made in order to catalogue the languages, explain their diversity and discover how they are mutually related. A ground-breaking moment in this pursue was a lecture given by William Jones who introduced to the wider scholar interest the idea of a common ancestor for languages which today are called Indo-European. One of the most enthralling questions that arose since the lecture is the question of the homeland (Urheimat) of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) people. Last decades have been the time of passionate discussions and many new arguments and theories have been provided. However, the final answer of where the Urheimat was is still debated and scholars haven’t found the consensus yet[1].

The PIE is not only a scholar excitement. The newest discoveries are published in newspapers, e.g. in The New York Time (2012), where an article was published suggesting that the answer to the homeland question has been answered[2]. It was also used in a computer game, as Frankfurter Allgemeine informs[3].

There are two most important competing hypotheses. The first one says that the Proto-Indo-European people and language come from Pontic-Caspian steppes where they lived about 4000 BC (Kurgan hypothesis). According to the second, the Urheimat is to be looked for in Anatolia about 7000 BC. Other theories place the homeland in Armenia, in the area of ancient Bactria-Sogdiana and other locations. According to Asya Pereltsvaig, the Kurgan hypothesis is the most commonly accepted one and followed by Anatolian and Armenian[4]. Luca Cavalli-Sforza and Alberto Piazza suggest that both major hypotheses can be compromised and are not excluding one another[5].

The aim of this essay is to briefly present the current state of research by presenting and comparing the most popular theories in the following areas: linguistic, archaeological and genetical.

Hypotheses

There are many theories about the homeland of Proto-Indo-Europeans. Since 1786 when William Jones gave the speech about the possible common ancestor of Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and other languages, many hypotheses have been proposed by various scholars. William Jones himself suggested later that the Urheimat lay in greater Iran. Many theories followed this first one. Nowadays there are a few that are competing in the scholarly world.

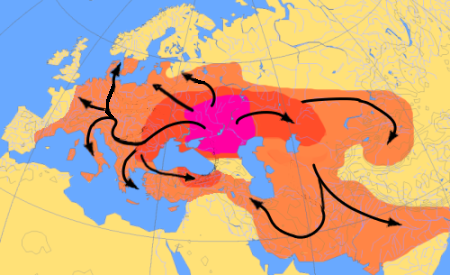

Scheme of Indo-European migrations from ca. 4000 to 1000 BC according to the Kurgan hypothesis. source: WIkipedia

The first one was first formulated by Marija Gimbutas in the 1950s who placed the homeland in Eurasian steps in today’s Ukraine and Russia. According to this, the Late PIE must have started its spread and division after 4000 BC. The second one places the homeland in Anatolia (Turkey). This was first developed by Colin Renfrew in 1987. According to him, PIE has much older roots and its expansion started about 7000 BC. The third one is known as Armenian hypothesis and locates the homeland in Armenia about 5000 BC. There are many other but, according to Asya Pereltsvaig, they do not gain much support in the academic world[6].

Looking for the homeland of the Proto-Indo-European people we must ask which phase of their history we are interested in. The Proto-Anatolian problem is exemplary for this issue as it significantly differs from the other branches of the language family. It may even be considered a cousin rather than a sibling to other PIE languages[7].

Linguistic

A comprehensive overlook of the Nordic languages in their old world language families (Indo-European and Uralic). By: attanatta https://www.flickr.com/photos/austinaronoff/17466175495

In the core of the steppe hypothesis lies the fact the many PIE words refer to stock farming, wheeled vehicles, but not in a great extent to agriculture. Therefore, the place and time that would best suit the reconstructed vocabulary can be found in Pontic-Caspian steppe among pastoralists rather than farmers. The proposed time for post-Anatolian PIE is 4000-3500 BC (as the Anatolian branch had diverged as first and before all the mentioned vocabulary was fully developed)[8].

The Anatolian hypothesis has not been based on linguistic research but rather on archaeological evidence. However, as this approach ties Proto-Indo-Europeans to agriculture, some support in the reconstructed vocabulary has been found. J.P. Mallory lists 27 words associated with farming in the PIE[9]. The study of Remco Bouckaert et al. has provided a model using Bayesian phylogeographic approaches. The result of the computer simulation of the language change and expansion supports the Anatolian origin. It was based on basic vocabulary data from 103 ancient and contemporary languages from Indo-European family[10]. This model is, however, not in accordance with the result of comparing the linguistical and archaeological data. David W. Anthony and Don Ringe point out that it is not possible to be reliable because of the wheel connected vocabulary[11].

The vocabulary can help us establish the date after which Proto-Indo-European must have been spoken. This date is about 4000-3500 BC and comes from linguistic and archaeological research. The axis of this thesis is the invention of the wheel and the presence of the relevant vocabulary[12]. Mallory, however, suggests that the spread of such vocabulary might be later than the beginning of language expansion and the similarities are due to passing the invention through the linguistic continuum. This process could not be detected from a later time perspective[13]. David A. Anthony and Don Ringe disagree with this statement withal and claim that such a borrowing could be detected even in the case of the PIE[14].

Another linguistic clue that we have are loanwords. As the adjacent languages influence each other, the result of linguistic exchange might help us find the location of the tribe that used the language. Mallory and Adams mention reciprocal influences with the following language families: Urali, Afro-Asiatic (here Semitic) and Kartvelian[15]. A study by Aleksi Sahala proves the existence of loanwords between Proto-Indo-European and Sumerian Language[16]. However, Mallory and Adams claim that the presence of such vocabulary might not be a result of direct contact. It might be the result of adopting Wanderwörter, words that travel long distances in cultures or the result of shared distant ancestry[17] and the location of other language families’ homelands is also not well known[18]. Potential loanwords from Semitic, Kartevelian, Sumerian and Egyptian languages alongside with the supposed glottalic sound system of early PIE made Thomas V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov place the Urheimat in eastern Anatolia and Armenia (so called Armenian hypothesis)[19]. The glottalic hypothesis is questionable, but their analysis provided support for Renfrew’s Anatolian hypothesis[20].

Archaeological

The increasing knowledge about prehistorical peoples can help us find candidates for the those whose mother tongue was Proto-Indo-European, at least at one of its stages. Both major theories can provide strong ties to archaeologically well known peoples and cultures. The wheel invention and horse domestication are proven by the findings in Pontic-Caspian steppes. The Anatolian supporters connect the spread of PIE with a demographic migration that brought agriculture to Europe from Asia Minor.

Many researchers support the Pontic-Caspian origin. Robert S.P. Beeks asserts that the archaeological cultures of Southern Russia are the best choice for the Proto-Indo-Europeans. Evidence of wheel usage as other technological advances correspond to the linguistic data we possess and therefore an assumption that Late PIE was spoken by those people is probable, even though there might have already existed different dialects of the language[21]. A similar point of view is represented by David W. Anthony who even states that other proposals are increasingly difficult to correspond with new evidence[22]. The borderline is commonly set at the moment of the invention of the wheel. The earliest archaeological proof of the usage of the wheel comes from Bronocice (Poland) and is estimated to be 5500 years old[23]. As PIE has a rich vocabulary connected with wheeled transport, this must be the date after which the languages have started their spread.

Tying the Yamna culture to Proto-Indo-Europeans is, however, not fully satisfactory. According to J. P. Mallory, there is a lack of a link between this culture and Proto-Indo-Iranians or Indo-Aryans. No underlying culture that would connect the Pontic steppes and their homeland has been discovered. Similar problems have to be solved as far as Ancient Greece and Anatolia are concerned[24].

Therefore, another solution was proposed. Colin Renfrew has associated the archaeologically attested migration of agricultural economies from Anatolia to Greece and the rest of Europe with the spread of Proto-Indo-European[25]. However, as J.P. Mallory points at, a prospective archaeology cannot easily tie the spread of PIE either with the spread of agriculture from Anatolia or with the domestication of horses and thus a more aggressive expansion of peoples from the stepplands[26]. On the other hand, this is claimed to be not true by David W. Anthony and Don Ringe, according to whom the Pontic-Caspian homeland fits into archaeological data about migrations and linguistic data concerning the chronology of the PIE divisions[27].

Genetical

Genetical research is relatively new and therefore a very exciting way of looking into the past and thus arousing many discussions. The investigation has so far proved that both hypotheses are possible as there were migrations originating from both Anatolia and Pontic-Caspian steppes in time periods required by the provided models. According to studies by Iosif Lazardis et al. there were even three migration waves from the steppes[28]. Notwithstanding the optimism of the researchers, others, like Paul Heggarty, doubt that the genetical-migration evidence can be easily tied to the whole PIE group of languages and associates it only with groups whose descendants spoke Slavic languages[29]. On the other hand, according to Harald Haarmann, the genetical research has proved that there was no massive migration from Anatolia to Europe, which proves, according to him, that the spread of Proto-Indo-European could not have its source there[30]. Academia has not yet reached a consensus on the matter of the genetical evidence of peoples’ migrations.

There are also methodical problems arising when genetical evidence is to be used in pursuing the answer to the homeland question. According to Mallory, the migration discovered using genetical methods cannot be tied to a linguistic movement[31]. The matter is concluded by Will Chang et al. Both hypotheses are plausible as far as genetic research on migrations is concerned. Therefore, the main focus should be directed to archaeological and linguistic evidence[32]. This later can be tied to a particular population change to create a more solid picture of the past.

Conclusion

The question about where the Proto-Indo-European homeland lay is still open. Although the consensus is nearer, and the Pontic-Caspian origin is emerging as the major theory, others still hold strong arguments and not all the doubts have been dispelled. There are also alternative solutions provided. The wheel problem might be explained by the hypothesis that Pre-Anatolian diverged from Proto-Indo-European before 4000 BC, as Bill Darden suggests[33].

Future research offers a prospect of intriguing discoveries. Maybe it is possible to reconcile the two competing theories: Kurgan and Anatolian? Maybe the first emergence of PIE occurred much earlier than the steppes and Anatolian branches are offspring of the early PIE. Then the later stage of PIE spread from the steppes into most of the currently know IE languages. This might be true, but the split must have happened not much prior to the invention of the wheel[34]. Much can be hoped from the research about Yamna culture that is going to be led by Volker Heyd from Helsinki University[35]. This continuous urge to explore the past makes us hope that it will be illuminated and it will reveal to us its secrets.

Bibliography

- Anthony, David W., The Horse, the Wheel and Language (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007).

- Anthony, David W. and Don Ringe, “The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archeological Perspectives”, Annual Review of Linguistics (2015). 199-219.

- Beekes, Robert S.P., Comparative Indo-European Linguistics. An Introduction (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company 1995).

- Bouckaert, Remco et al., “Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family”, Science 337.2012 (24 August 2012). 957-960.

- Callaway, Ewen, “European languages linked to migration from the east” (12 February 2015), retrieved 7 May 2018 from https://www.nature.com/news/european-languages-linked-to-migration-from-the-east-1.16919.

- Chang, Will, Chundra Cathcart, David Hall, Andrew Garrett, “Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis”, Language Volume 91, Number 1 (March 2015). 194-244.

- Gamkrelidze, Thomas V. and V. V. Ivanov, “The Early History of Indo-European Languages”, Scientific American, (March 1990): 110-116.

- Haarmann, Harald, Auf den Spuren der Indoeuropäer (München: C.H. Beck 2016).

- Lazaridis, Iosif, Nick Patterson, Johannes Krause et al., “Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans”, Nature2014 (18 September 2014), 409-413.

- Mallory, J. P. and D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006).

- Małecki, Rafał, Ojczyzna Wozu: Europa czy Bliski Wschód, Wiedza i Życie (8/19986), retrieved from an Internet copy (12 May 2018): http://archiwum.wiz.pl/1996/96083600.asp.

- Pereltsvasig, Asya, Languages of the World. An introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 2012).

- Piazza, Alberto and Luigi Cavalli-Sforza, “Diffusion of genes and languages in human evolution”, Proceedings Of The 6th International Conference on the Evolution of Language (Rome: World Scientific 2006). 255-266.

- Renfrew, Colin, Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins (London: Jonathan Cape 1987).

- Sahala, Aleksi, Sumero-Indo-European Language Contacts (Helsinki 2013) retrieved 8 May 2018 http://www.ling.helsinki.fi/~asahala/asahala_sumerian_and_pie.pdf.

- Uotinen, Suvi, “Another ERC Advanced Grant secured for the University of Helsinki: Archaeologists to collaborate with natural scientists” (3 May 2018), retrieved 7 May 2018 from https://www.helsinki.fi/en/news/language-culture/another-erc-advanced-grant-secured-for-the-university-of-helsinki-archaeologists-to-collaborate-with-natural-scientists.

Footnotes

[1] J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006), 460.

[2] Nicholas Wade, “Family Tree of Languages Has Roots in Anatolia, Biologists Say”, The New York Times 24 Aug. 2012: A9.

[3] Ulf von Rauchhaupt, “Auf Wenja schreit es sich am besten“, Frankfurter Allgemeine 05 Apr. 2016, retrieved 17 May 2018 http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/medien/steinzeitsprachen-im-videospiel-far-cry-primal-14160446.html.

[4] Asya Pereltsvasig, Languages of the World. An introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2012), 22-24.

[5] Alberto Piazza, Luigi Cavalli-Sforza, “Diffusion of genes and languages in human evolution”, Proceedings Of The 6th International Conference on the Evolution of Language (Rome: World Scientific 2006), 258-259.

[6] Asya Pereltsvasig, Languages of the World. An introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2012), 23.

[7] David W. Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel and Language (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007), 47-48.

[8] David W. Anthony and Don Ringe, “The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archeological Perspectives”, Annual Review of Linguistics, (2015): 202.

[9] J.P. Mallory, “Twenty-first century clouds over Indo-European homelands”, Journal of Language Relationship. Вопросы языкового родства, 9 (2013): 149.

[10] Remco Bouckaert et al. “Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family”, Science vol. 337.2012, (24 August 2012), 957.

[11] David W. Anthony, Don Ringe, “The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archeological Perspectives”, Annual Review of Linguistics (2015): 202-206.

[12] David W. Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel and Language (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007), 59.

[13] J. P. Mallory, D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford University Press: Oxford 2006), 455.

[14] David W. Anthony, Don Ringe, “The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archeological Perspectives”, Annual Review of Linguistics (2015) 205.

[15] J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006), 444.

[16] Aleksi Sahala, Sumero-Indo-European Language Contacts (Helsinki 2013), retrieved 8 May 2018 http://www.ling.helsinki.fi/~asahala/asahala_sumerian_and_pie.pdf.

[17] J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006), 445.

[18] J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006), 456.

[19] Thomas V. Gamkrelidze and V. V. Ivanov, “The Early History of Indo-European Languages”, Scientific American, (March 1990): 113-115.

[20] David W. Anthony, Don Ringe, “The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archeological Perspectives”, Annual Review of Linguistics (2015): 202.

[21] Robert S. P. Beekes, Comparative Indo-European Linguistics. An Introduction (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company 1995), 50-51.

[22] David W. Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel and Language (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007), 458.

[23] Rafał Małecki, Ojczyzna Wozu: Europa czy Bliski Wschód, Wiedza i Życie (8/1996), retrieved from an Internet copy (12 May 2018): http://archiwum.wiz.pl/1996/96083600.asp.

[24] J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006), 452.

[25] Colin Renfrew, Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins (London: Jonathan Cape 1987).

[26] J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006), 452-453.

[27] David W. Anthony and Don Ringe, “The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archeological Perspectives”, Annual Review of Linguistics (2015): 208.

[28] Iosif Lazaridis, Nick Patterson, Johannes Krause et al.. “Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans”, Nature 513.2014 (18 September 2014): 409-413.

[29] Ewen Callaway, “European languages linked to migration from the east” (12 February 2015), retrieved 7 May 2018 from https://www.nature.com/news/european-languages-linked-to-migration-from-the-east-1.16919.

[30] Harald Haarmann, Auf den Spuren der Indoeuropäer (München: C.H. Beck 2016), 31.

[31] J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006), 450-451.

[32] Will Chang, Chundra Cathcart, David Hall, Andrew Garrett, “Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis”, Language Volume 91, Number 1 (March 2015), 196.

[33] David W. Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel and Language (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007), 75.

[34] David W. Anthony and Don Ringe, “The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives”, Annual Review of Linguistics (2015): 206.

[35] Suvi Uotinen, “Another ERC Advanced Grant secured for the University of Helsinki: Archaeologists to collaborate with natural scientists” (3 May 2018), retrieved 7 May 2018 from https://www.helsinki.fi/en/news/language-culture/another-erc-advanced-grant-secured-for-the-university-of-helsinki-archaeologists-to-collaborate-with-natural-scientists.